IHG bookings are usually discussed in cents-per-point terms: how expensive the points are, whether they’re worth buying, and how the maths compares to paying cash.

That lens is often sufficient.

But at some properties, switching into the points pricing system does something else entirely. It moves the booking onto a different pricing scale, one where room-type distinctions that exist in cash pricing simply disappear.

This piece is about that specific case.

Two pricing systems, one hotel

IHG operates two parallel pricing systems.

Cash pricing

Rooms are priced horizontally

Smaller rooms are cheaper

Larger or better-laid-out rooms cost more

Room hierarchy is explicit and preserved

Points pricing

Rooms are priced vertically

“Standard rooms” collapse into a single award bucket

Physical room distinctions often disappear

Value is expressed in points, not room type

These systems coexist, but they do not behave the same way.

Viewing a booking through the points interface is what bridges them.

What actually changes when you enter the points system

The moment you toggle into points availability, IHG stops asking:

“Which room are you buying?”

and starts asking:

“Are you booking into the standard-room reward bucket?”

At many properties, multiple cash room types map into that same internal “standard room” category. Once the booking enters the points universe, those rooms converge onto a single pricing ladder.

That effect is the source of value. I’ll refer to it as ladder convergence.

The Kimpton Fitzroy example

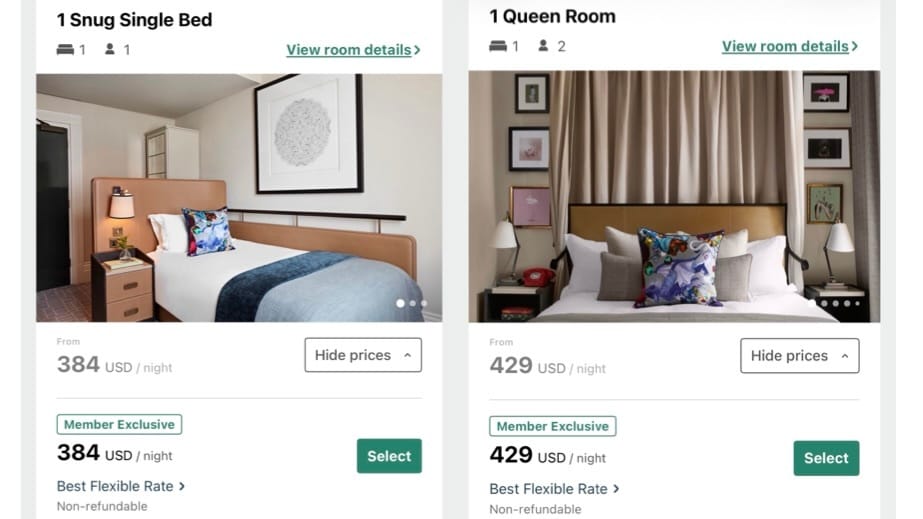

Cash pricing shows room hierarchy. The Queen has a $45 premium over the Snug Single on the same night.

In cash, the hotel presents a familiar hierarchy:

Snug Single: ~$384

Queen Room: ~$429

That $45 spread reflects room hierarchy. If you want the better room, you pay more.

Now view the same night through the points interface.

Once points pricing is active, both rooms sit on the same award ladder, anchored to a ~60,000-point full standard award for this date, as shown in the app. The only difference between them is their cash-only price outside the points system.

Rung | Snug Single | Queen Room |

|---|---|---|

Cash-only price | $384 | $429 |

Full points | 60,000 pts | 60,000 pts |

Points + Cash | 50,000 pts + $65 | 50,000 pts + $65 |

40,000 pts + $125 | 40,000 pts + $125 | |

30,000 pts + $179 | 30,000 pts + $179 | |

25,000 pts + $202 | 25,000 pts + $202 | |

20,000 pts + $224 | 20,000 pts + $224 | |

Lowest rung | 10,000 pts + $269 | 10,000 pts + $269 |

Ladders converge: there is no separate ladder for the Queen. Once the booking enters the points universe, both rooms map to the same internal “standard room” award category and are governed by the same pricing scale.

What the ladder is really telling you

For the Snug Single, the analysis is straightforward. A full 60,000-point redemption displaces $384 of cash, producing a strong outcome by IHG standards. That is the correct decision.

The important point is that the same conclusion applies to the Queen Room.

Because the ladder is calibrated to the cheapest standard room, moving into points pricing effectively gives you the Queen Room’s $45 premium for free at every rung.

However, that premium is already embedded in the baseline 60,000-point valuation, which is why partial redemptions below the full award remain sub-optimal.

Why 60,000 points is the correct answer here

Every rung below full points represents a conscious choice to retain points in exchange for cash.

The trade-offs look like this:

Step | Cash paid to keep points | Points retained | Implied “purchase” price |

|---|---|---|---|

60k → 50k | $65 | 10k | 0.65 cpp |

60k → 40k | $125 | 20k | 0.625 cpp |

60k → 30k | $179 | 30k | 0.597 cpp |

60k → 20k | $224 | 40k | 0.56 cpp |

60k → 10k | $269 | 50k | 0.538 cpp |

Once framed this way, the decision stops being ambiguous.

IHG points can be purchased with high regularity around 0.5 cpp. Paying more than that simply doesn’t make sense during such times.

That leaves only two cases:

• If you already have the points, you should redeem all 60,000.

• If you do not have the points, you should buy them and redeem all 60,000.

In this case, right now, while points can be purchased directly around 0.5 cpp, there is one correct answer. Points + Cash is useful here only because it reveals how the pricing system works. It does not improve the outcome once the full points option is available.

Why standard cpp analysis loses precision here

Conventional points analysis assumes:

Points substitute directly for cash

Value should be measured per point

The correct comparison is always points versus cash

That logic fails because the act of using points changes the pricing rules themselves.

You are not asking:

“Are 60,000 points worth $429?”

You are asking:

“Is it worth exiting a pricing framework that would otherwise force me to pay $45 more for the same room?”

Those are different questions.

This is why cpp-only analysis consistently under-explains outcomes like this. It answers the wrong problem.

Structural, but not universal

This behaviour follows directly from how IHG defines “standard room” inventory.

When multiple cash room types map into that category, ladder convergence becomes possible.

At properties with only a single standard room type, it does not.

Points pricing creates the effect.

Points + Cash merely provides partial access to it.

What this means in practice

Points pricing can sometimes place you in a different market entirely, one where room hierarchies flatten and cash premiums vanish.

That does not mean:

Points are always better than cash

cpp no longer matters

Points + Cash is inherently attractive

It means something narrower and more useful.

If you already know which room you want, entering the points pricing system can sometimes let you buy that room under a different set of rules.

In this case, once those rules are visible, the optimal decision is clear.

Why this keeps getting missed

Most commentary circles the behaviour without honing in on it precisely.

Discussion tends to fall into two arenas:

Treating Points + Cash as point manufacturing

Treating cpp as the only valid lens

Neither perfectly captures what is actually happening.

What matters is not the headline “cpp” attached to the points.

What matters is which pricing framework you are operating inside.

Once that framework is clear, the optimal decision follows.